I’ve just returned from SILENT LAUGHTER WEEKEND at London’s Cinema Museum. The fourth such event run by the lovely folk at Kennington Bioscole, these are now a real highlight of my year, and I was privileged to have some involvement in selecting and presenting a few films. Of course, we’re lucky to have silent comedies so freely available on DVD, YouTube and everywhere else, but the real way they’re meant to be seen is like this: on a big screen, as a shared experience with other cinemagoers, and with live musical accompaniment. Stand up and take a bow, John Sweeney, Meg Morley. Neil Brand, Costas Fotopoulos, Cyrus Gabrysch, whose wonderful playing brought these films to life. To hear the expert introductions of historians such as Kevin Brownlow and David Robinson only heightened the experience. Here’s part one of a review of the weekend. Part two to follow!

I’ve just returned from SILENT LAUGHTER WEEKEND at London’s Cinema Museum. The fourth such event run by the lovely folk at Kennington Bioscole, these are now a real highlight of my year, and I was privileged to have some involvement in selecting and presenting a few films. Of course, we’re lucky to have silent comedies so freely available on DVD, YouTube and everywhere else, but the real way they’re meant to be seen is like this: on a big screen, as a shared experience with other cinemagoers, and with live musical accompaniment. Stand up and take a bow, John Sweeney, Meg Morley. Neil Brand, Costas Fotopoulos, Cyrus Gabrysch, whose wonderful playing brought these films to life. To hear the expert introductions of historians such as Kevin Brownlow and David Robinson only heightened the experience. Here’s part one of a review of the weekend. Part two to follow!

The weekend began with THE NIGHT CLUB (1925), starring Raymond Griffith (promoted as ‘The New Sheik of Slapstick!”). His first starring feature, it is a wonderful vehicle for his understated, unique comic style. The film launched his career in features with a high pedigree; produced and co-scripted by Cecil B DeMille, it was directed by his protégées Paul Iribe and Frank Urson and based on a play by DeMille’s brother.

This is a farcical tale in which Griffith is stood up by his bride, renounces all women but has to undergo an arranged marriage to inherit a fortune. He genuinely falls in love with his arranged bride (Vera Reynolds), but she thinks he’s only after her for the money. A despondent Griffith pays a bandit (Wallace Beery) to bump him off, but Vera finds out the truth and they are reconciled. Now Griff’s only problem is to tell the bandit that no, thank you, he doesn’t want to die anymore…

This is a farcical tale in which Griffith is stood up by his bride, renounces all women but has to undergo an arranged marriage to inherit a fortune. He genuinely falls in love with his arranged bride (Vera Reynolds), but she thinks he’s only after her for the money. A despondent Griffith pays a bandit (Wallace Beery) to bump him off, but Vera finds out the truth and they are reconciled. Now Griff’s only problem is to tell the bandit that no, thank you, he doesn’t want to die anymore…

It’s a complicated story and even that summary doesn’t take account of many of the tangents and subplots that arise. It’s easy to see why it was a failure as a play, but as a Griffith vehicle it succeeds admirably. Our hero wins through with a wonderfully understated performance that sells the far-fetched story, and shows his trademark skill in creating laughter with subtle gestures and facial expressions.

There are also great performances from Beery, William Austin and Louise Fazenda, not to mention some great suicide gags and lovely location shooting on the dusty paradise of Catalina Island.

Director Eddie Sutherland contended that Griffith’s failing as a comic was that he tried to mix too many styles, but the inclusion of sight gags and slapstick alongside more gentle material makes films like THE NIGHT CLUB much more entertaining than many of the light comedies of the era.

Griffith’s best films were yet to come, as he refined his suave, sly style; his best surviving films are probably PATHS TO PARADISE and HANDS UP. THE NIGHT CLUB, however, remains a fun and different comedy. By the way, if you’re wondering where the night club of the title comes in… it doesn’t. Kevin Brownlow explained in his introduction that this was a side effect of the studios’ block booking system. Often films were sold to exhibitors before they were filmed or even written. Paramount had promised a film called ‘THE NIGHT CLUB’, so they delivered a film called ‘THE NIGHT CLUB’, even though their new story had nothing at all to do with one!

Next it was on to a programme of British shorts, titled THE BRITISH ARE COMING and presented by Tony Fletcher. Now, these can be a mixed bag. There are some fantastic British silent comedies, but many are a bit too polite and ponderous. Certainly, they were created in a different idiom to the American model of silent comedy.This programme had a higher batting average than many, showcasing some offbeat efforts.

‘BOOKWORMS’, made in 1920, is a charming little vehicle for Leslie Howard. Written by A.A. Milne (author of the Winnie-the-Pooh stories), it shows Milne’s literary instincts in a witty modern fairytale pastiche. Substituting suburban villas for castles and fiery housemaids for dragons, this is an updated Rapunzel-style tale of Howard’s attempts to contact Pauline Johnson, who is locked away by her Aunt and Uncle, and made to read books all day. Howard’s love note arranging a rendezvous, sent inside her library book, also reaches three other people, resulting in a farcical meeting of several different characters, each thinking the other has sent it. This is a mild, but very charming tale. Much of the humour comes from the breaking of the fourth wall, especially in the intertitles.

This was a pet tactic of director Adrian Brunel, who loved to play with the medium of film. More of Brunel’s whimsical humour was seen in CROSSING THE GREAT SAGRADA. A spoof travelogue, this skewers the pomoposity of the genre superbly. Again, much of the humour coems through intertitles, juxtaposition of images and bizarre use of stock footage. In its sublime silliness, the short anticipates Spike Milligan’s work (especially sketches from ‘Q’, like ‘First Irish Rocket to the Moon’)

Also experimental was THE FUGITIVE FUTURIST, in which an inventor produces a magic device that shows visions of the future. Through the magic of double exposure, animation and an effect that makes the emulsion seem to melt off the film, we see waves lapping at the shores of Trafalgar square, Tower Bridge turned into a monorail, and houses that build themselves. A bizarre little film!

There was a chance to glimpse behind the scenes at the film industry (and film fandom) with STARLINGS OF THE SCREEN. This short chronicles the progress of a competition run by Picture Show magazine, whereby 3000 young ladies entered to be in with a chance of winning a film role; kind of ‘THE X FACTOR’ of its day! The 15 shortlisted provincial candidates are seen trying their hardest to act at a series of screen tests at Oswald Stoll’s studios. Also on hand is comic actor Moore Marriott, later best known as one of Will Hay’s sidekicks, who puts the girls through their paces in a series of short little sketches. This was a great little item: a fascinating time capsule, often (unintentionally) hilarious. There was also a touch of poignancy in the doomed ambitions of the film hopefuls, who simply didn’t have ‘it’ and would soon return to obscurity. Nancy Baird of Glasgow, and Sheilagh Allen of Londonderry, whatever became of you?

So far, so good. The only one of these films to disappoint was ‘BEAUTY AND THE BEAST’. Starring Guy Newall & Ivy Duke, this too played with the medium of cinema, having a prologue breaking the fourth wall, in which Duke & Newall invite the public to join them in their dressing rooms preparing for the film. The story itself was the tale of Duke’s perpetual discomfort caused by her woollen underwear. At the theatre, Newall is sat behind her, absentmindedly fiddles with a thread he sees dangling from the bottom of her chair and soon has unravelled her entire vest. It was a nice little idea for a throwaway gag, but stretching it out to almost half an hour was fairly infuriating! I could have seen Lloyd or Keaton doing a similar gag, but as a little aside, rather than building a whole film around it! Nevertheless, an interesting little item, and overall this showed that British films were often very creative and playful.

After lunch, I was thrilled to be able to present an overview of CHARLEY CHASE. Chase is one of my absolute favourite silent (and sound comedians), and he’s often been a neglected figure, so it’s always a pleasure to show his films to new audiences. The 1920s, with their increased focus on human comedy, were Chase’s decade. In front of the camera, he played an eternally embarrassed young man, while behind it he was an enormously inventive, prolific and consistent comedy craftsman.

After lunch, I was thrilled to be able to present an overview of CHARLEY CHASE. Chase is one of my absolute favourite silent (and sound comedians), and he’s often been a neglected figure, so it’s always a pleasure to show his films to new audiences. The 1920s, with their increased focus on human comedy, were Chase’s decade. In front of the camera, he played an eternally embarrassed young man, while behind it he was an enormously inventive, prolific and consistent comedy craftsman.

An extract from ALL WET (1924) provided an early example of a classic Chase situation, escalating from simple, believable beginnings to peaks of absurdity. Charley is on his way to meet a train in his car; he helps another motorist out of a mud puddle, and in doing so becomes stuck himself. His attempts to free the car end in it being completely submerged, necessitating Charley’s repairs of the car from underwater. ALL WET builds gags brilliantly, and is a fine example of the teamwork between Chase and its director, future Oscar-winner Leo McCarey (who once said “Everything I know, I learned from Charley Chase”).

Together Chase and MccCarey thrived off each other, developing a unique style of intricate storytelling. When Chase’s films were expanded to two reels, they were able to use the extra space to construct beautifully elaborate farces, mini-masterpieces packed with gags, situations and great characters. To illustrate this, we saw large excerpts from ‘WHAT PRICE GOOFY’, ‘FLUTTERING HEARTS’ and ‘THE WAY OF ALL PANTS’, the latter getting some of the biggest laughs of the weekend with its split-second timed multiple exchanges of trousers.

Two things struck me forcefully while selecting the clips:

1 – it’s incredibly hard to take excerpts out of Chase’s films, as they are so tightly and masterfully constructed.

2 – Chase really realised the value of his supporting casts. Perhaps it was background as a director, but he never seems egotistical about his own performances, always allowing others to shine; his films are true ensemble pieces. Oliver Hardy, Katherine Grant, Gale Henry, Thelma Todd, Tom Dugan, Vivian Oakland and Buddy the Dog are just some of the performers given great opportunities in the films we saw.

The closing scenes from ‘THE PIP FROM PITTSBURG’ showcased Charley’s illustrious career in talkies, and we finished off with the complete ‘MIGHTY LIKE A MOOSE’. The apotheosis of Charley’s taking a simple idea to ridiculous extremes, this tale follows him and and his wife as they both have plastic surgery, fail to recognise each other and embark on an affair! This has righty been recognised as a masterpiece, and has been added to the USA’s National Film Registry along with other classics like ‘THE GENERAL’ and ‘BIG BUSINESS’.

It was a real delight to hear the laughter at Chase’s films, with several people in the audience commenting that it was their first time seeing them. Charley didn’t live long enough to see his work being appreciated; if only he could have heard the response his films got on Saturday…

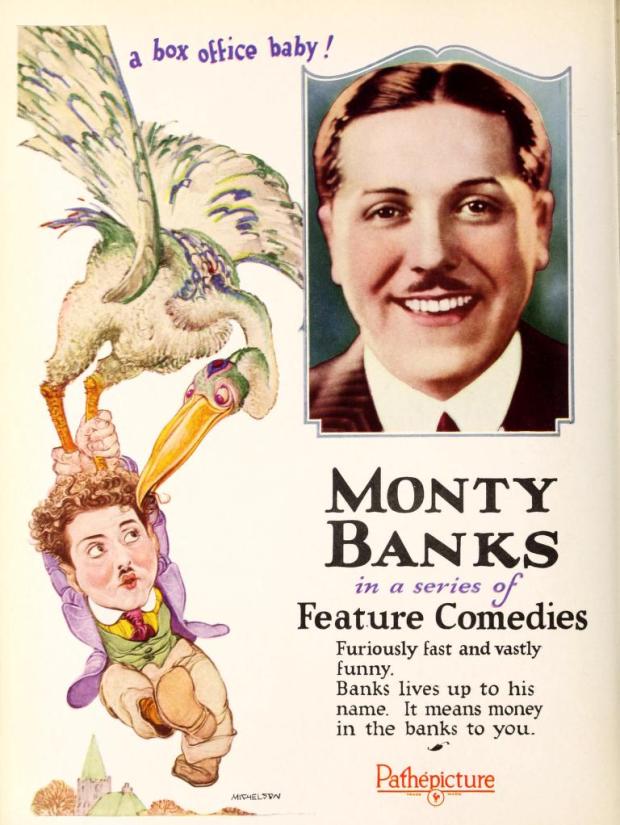

Also in the comedy of embarrassment mould was Monty Banks’ 1927 feature ‘A PERFECT GENTLEMAN’. We saw it in a pristine 35mm copy from the BFI, albeit with Spanish intertitles. Monty was, for my money, one of the hardest working silent comedians. He was an Italian, real name Mario Bianchi, who arrived in the US in 1915. He spoke very little English, but through hard work and a good deal of good luck, scraped by in a series of Chaplinesque film roles. These included supporting Roscoe Arbuckle, who gave him his new screen name. Making a series of comedies for obscure and independent companies, he eventually found a toehold in the industry with a cheerful little character, trying his best to be dapper, but always on the back foot. In the 1920s he shifted focus to vehicles with a Lloydian mix of comedy with thrills and speed, turning out a series of features that pitted him against racing cars, speedboats and runaway trains. From 1926, Pathé had been promoting him as Lloyd’s successor, but had more or less given up on him by the time of ‘A PERFECT GENTLEMAN’. With some evidence of budgets being cut, it features less of the high-speed stunt climaxes, but makes up for it with brilliantly gag-packed sequences and situation comedy. Monty works in a bank, and is due to marry the president’s daughter. En route to his wedding he innocently becomes drunk; suffice to say, his wedding does not end well, especially as he spends much of the time trying to kick his future mother-in-law in the rear!

Meanwhile, Monty’s colleague has robbed the bank, planning to pin the robbery on Monty. Waking with a terrible hangover to a broken engagement, Monty decides to leave town, but mixes his bags, and ends up with the stolen money. The rest of the film takes place on board a ship and follows Monty’s attempts to:

- foil the crooks trying to get the money back

- win back his girl who is aboard the ship

- return the money to her father and prove his innocence.

He might be on a ship, but plain sailing, it ain’t! A new complication arises as Monty is constantly caught in compromising situations with the purser’s wife, a running gag that has some brilliant variations. Best of all is a sequence where Monty, finding her unconscious, accidentally tears her dress off. His attempts to remedy the situation end up making even more of her clothes fall off, but he manages to improvise an entirely new outfit for her. A wonderful routine of physical comedy, in a film full of them; it’s the funniest Banks film I’ve yet seen.

Part of the credit is surely due to Clyde Bruckman, one of the very best silent gagmen, hired by Banks due to his work with Keaton & Lloyd. A PERFECT GENTLEMAN does indeed borrow some gags from the Keaton/Lloyd vehicles. Overall though, it shows Monty moving from a direct Lloyd influence to a more farcical style redolent of Charley Chase. In fact, this could have been the ideal vehicle to launch Chase in features. A great little film, and one of the highlights of the weekend for me. Nevertheless, however good performers like Banks or Raymond Griffith are, the following programme, KEATON CLASSICS, made it clear just why Buster Keaton has attained his mythical status in comparison to the more forgotten comics. Four authors – Kevin Brownlow, David Robinson, Polly Rose & David McLeod – presented their favourite sequences from Buster’s features. Each sequence was, of course, magnificent, and I almost felt like I was seeing them for the first time again. It was a lovely idea to have personal introductions, as Keaton means so many different things to so many people.

David Robinson praised the dramatic strength of OUR HOSPITALITY, reminding us that it was a stunning debut in feature directing (THE SAPHEAD was not directed by Keaton and THREE AGES planned as three shorts glued together, in case it didn’t work out; ergo, HOSPITALITY was BK’s first planned feature). He had picked the river scene that culminates in Buster’s dramatic plunge across a waterfall to rescue Natalie Talmadge, a sequence that gives me the shivers every time I see it.

Kevin Brownlow’s choice was the wonderfully action-packed Tong War sequence from THE CAMERAMAN, and David McLeod opted for the iconic cyclone climax of STEAMBOAT BILL, JR. Most fascinating of all was Polly Rose, a newcomer to writing about BK; an editor by trade, she was ideally placed to share discoveries about how Keaton achieved his visual effects walking into the cinema screen in SHERLOCK, JR. Through her research, she also shared discoveries about alternate versions of the scene, in which Buster seemed to enter the screen on a beam of light shone from his projector, before being spat back out into a tangle of film. Polly shared evidence of this version being previewed from at least three trade papers, and found clues in publicity stills that point to the action that might have occurred. A fascinating theory and who knows? Maybe one day one of those preview prints will turn up. Stranger things have happened!

I know Keaton’s films so well by know that I sometimes take for granted how incredible they are. Seeing excerpts like this from different films reminded me just how diverse and special his films were, for not just his performances and gags, but also his storytelling, stunts and technical wizardry, not to mention that intangible quality that makes him so compelling.

How to follow four of Keaton’s finest sequences? Step up to the plate, Beatrice Lillie! Miss Lillie made only 7 films in her long career, and 1926’s EXIT SMILING is her sole silent. Nevertheless, her brief stay in Hollywood elicited devotion from the West Coast royalty; Chaplin described her as “my female counterpart”, while Buster Keaton guarded her hotel room door, “lying there like Old Dog Tray”. EXIT SMILING shows exactly why. One of the sadly few silent feature comedies to really show a female comedian to good advantage, it gives her opportunity for both great comic acting and genuine pathos. As Violet, Bea is a dogsbody with a travelling theatre company who longs to play the part of a vamp. She gets her chance to act not on the stage, but in real life, where she has to seduce a villain to save the man she loves. The scenes of her vamping the villain are simply brilliant, especially the moment where her pearl necklace disintegrates. If only sh e’d made more films!

e’d made more films!

EXIT SMILING was given a marvellously authoritative introduction by Michelle Facey, who summed up Bea’s career and appeal brilliantly. Accompaniment was by the wonderful Meg Morley. The screening was, in fact, of Beatrice Lillie’s personal 16mm copy of the film, and the personal connection of the evening didn’t end there. The last word must go to David Robinson, who shared his poignant story of attending a screening of the film with Beatrice Lillie in 1968.

“She was starting to forget things… They’d taken her to see the film ‘STAR’ that afternoon, so I asked her how she liked the film.

“What film?” she said. She didn’t seem like a star, she was just a little, worried old lady, who was always asking where her coat and purse were. It would be “Where’s my coat?” then “Where’s my purse?”

“So we went on and on, the coat, the purse, the coat, the purse… until the time came to go into the theatre.

“Where’s my coat?” she said, again. I told her I’d carry it, but she just said “I must have my coat”.

“We walked into the auditorium, and I was wondering what on earth was going to happen… then I noticed she was dragging the coat along behind her.

“Come along, Fido!” she said, and everyone roared with laughter. She came to life and kept doing these little bits of business, but knew exactly when to stop. Throughout the film, I heard the sound of her laughter.

Afterwards, I asked her what she thought of it.

“Oh, it was very good,” replied Beatrice Lillie, “and she’s so funny. And you know, she does things just like me!”

*Part two coming soon!*

Next, we have a brief dinner table scene where Stan enjoys some bathtub gin, and a card table scene, where Stan is playing against a count, and accuses him of cheating. This leads to him having to flee, disguising himself as a barber, a per the Valentino original. There are the brief bones of a comic barber sketch, before we cut into the flirtation scene I discussed at greater length in the last issue: Stan is attempting to escort the lady across a puddle in the street to an anachronistic yellow taxi cab. He lays down his coat, Walter Raleigh style, on top of the puddle. Stepping on it, Stan and escort disappear beneath the water; yup, it’s an early example of the famous L & H bottomless mudhole™! Here’s that scene, courtesy of the Cineteca’s YouTube account:

Next, we have a brief dinner table scene where Stan enjoys some bathtub gin, and a card table scene, where Stan is playing against a count, and accuses him of cheating. This leads to him having to flee, disguising himself as a barber, a per the Valentino original. There are the brief bones of a comic barber sketch, before we cut into the flirtation scene I discussed at greater length in the last issue: Stan is attempting to escort the lady across a puddle in the street to an anachronistic yellow taxi cab. He lays down his coat, Walter Raleigh style, on top of the puddle. Stepping on it, Stan and escort disappear beneath the water; yup, it’s an early example of the famous L & H bottomless mudhole™! Here’s that scene, courtesy of the Cineteca’s YouTube account: Take this film, for example. It’s mainly crude knockabout set in a department store, based rather obviously on Chaplin’s ‘THE FLOORWALKER’, right down to a central staircase prop. Here, it’s a precursor of the collapsing staircase Keaton used in 1921’s ‘THE HAUNTED HOUSE’. Did Buster get the idea from here? Whatever, it’s a perfect example of why Keaton was head and shoulders above performers like Aubrey; in ‘MAIDS & MUSLIN’, there’s no reason for the prop to be there, and the only gags that happen are people falling down it. Keaton, on the other hand, furnishes a reason for the staircase, and adds in a host of different variations on its use, that almost make it a character in itself.

Take this film, for example. It’s mainly crude knockabout set in a department store, based rather obviously on Chaplin’s ‘THE FLOORWALKER’, right down to a central staircase prop. Here, it’s a precursor of the collapsing staircase Keaton used in 1921’s ‘THE HAUNTED HOUSE’. Did Buster get the idea from here? Whatever, it’s a perfect example of why Keaton was head and shoulders above performers like Aubrey; in ‘MAIDS & MUSLIN’, there’s no reason for the prop to be there, and the only gags that happen are people falling down it. Keaton, on the other hand, furnishes a reason for the staircase, and adds in a host of different variations on its use, that almost make it a character in itself.

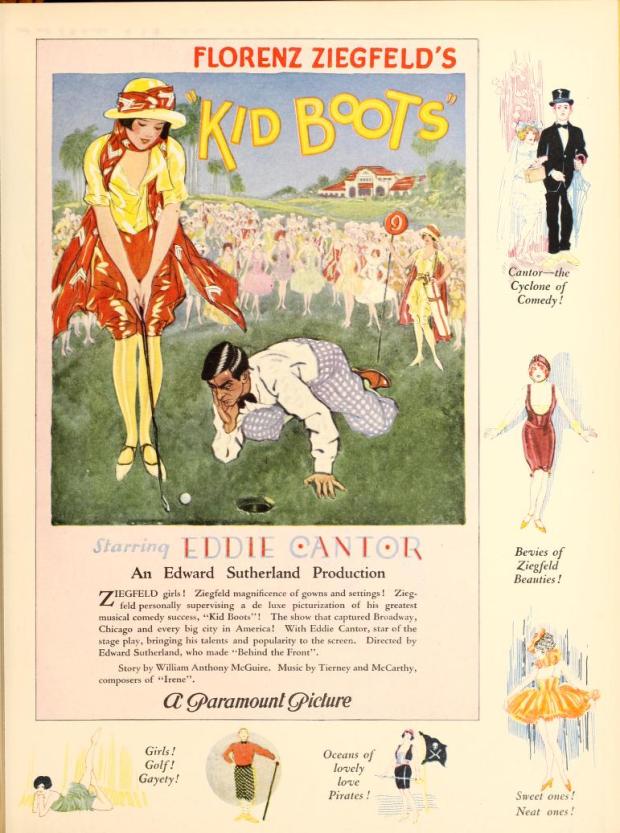

physio routine borrowed from Chaplin’s ‘THE CURE’, some high and dizzy thrills and a race to the courthouse that owe a debt to Lloyd’s ‘GIRL SHY’, and others more original. The highlight is a sequence where Kid Boots tries to make Clara jealous; his date has stood him up, but that won’t stop him! With the aid of a carefully placed screen door, he acts out a date with himself, baring his left arm and adding powder and a bracelet to simulate an imaginary girlfriend’s arm. Milking it for all it’s worth, he manages, in a pantomimic tour de force, to make it appear as though his ‘girlfriend’ can’t keep her hands off him. One of the funniest sequences we saw all weekend, this scene shows that Cantor, despite his predominantly verbal style, could master visual comedy as well as anyone.

physio routine borrowed from Chaplin’s ‘THE CURE’, some high and dizzy thrills and a race to the courthouse that owe a debt to Lloyd’s ‘GIRL SHY’, and others more original. The highlight is a sequence where Kid Boots tries to make Clara jealous; his date has stood him up, but that won’t stop him! With the aid of a carefully placed screen door, he acts out a date with himself, baring his left arm and adding powder and a bracelet to simulate an imaginary girlfriend’s arm. Milking it for all it’s worth, he manages, in a pantomimic tour de force, to make it appear as though his ‘girlfriend’ can’t keep her hands off him. One of the funniest sequences we saw all weekend, this scene shows that Cantor, despite his predominantly verbal style, could master visual comedy as well as anyone.