I’m blogging about comedy films seen at Kennington Bioscope’s SILENT LAUGHTER SATURDAY.

The first show of the afternoon was my turn to take the stage, presenting some shorts starring forgotten silent comedians. Time has slimmed down our view of popular culture so that a few names dominate – to the novice, Chaplin and maybe Keaton. To the slightly more dedicated film fan – Harold Lloyd, L & H, maybe at a pinch Harry Langdon. But silent comedy was a huge, rich field. So many talented names are unfairly forgotten, so it was a privilege to give these neglected talents some of the exposure they deserve. The four SILENT CONTENDERS I selected were great comedians all, at one time or another, tipped to be the next Chaplin, Keaton or Lloyd. That they didn’t quite make it was down was down to a variety of factors ( the studio system, time and place, personal demons, etc). Nevertheless, they turned out some work that I think is quite, quite wonderful in its own right.

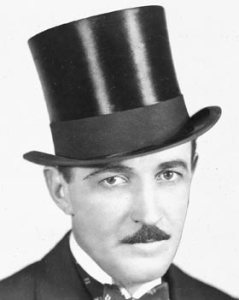

First up, was a comedian who pre-dated even Chaplin. Max Linder was one of the first international comedians. He was French, and making films from the mid 1900s for Pathe. These little films, with their cardboard painted sets, are primitive in their look, but Linder’s acting and directing are amazingly sophisticated for films over 100 years old. He played a suave yet often embarrassed boulevardier, a silk-hatted Romeo who got himself into farcical situations like fighting duels and hiding inside suits of armour. Chaplin was a fan, dedicating a photo to him “ To the one and only Max- the professor”. He could well have made it.

But then, WW1 intervened, just as Chaplinmania was striking. It was a fulcrum of Linder’s career for two reasons. For one thing, it decimated the French film industry. Linder managed to get around this by going to America to make films. At a time when anything vaguely. Chaplin-related was gold dust, an endorsement from the man himself was irresistible to the American studios. However, the war had also had a more personal, and sinister, impact on Linder; called up and severely injured in conflict, his experiences affected him mentally and physically. He would never quite have the strength to capitalise on his opportunities, and eventually his demons won with his 1925 suicide.

But then, WW1 intervened, just as Chaplinmania was striking. It was a fulcrum of Linder’s career for two reasons. For one thing, it decimated the French film industry. Linder managed to get around this by going to America to make films. At a time when anything vaguely. Chaplin-related was gold dust, an endorsement from the man himself was irresistible to the American studios. However, the war had also had a more personal, and sinister, impact on Linder; called up and severely injured in conflict, his experiences affected him mentally and physically. He would never quite have the strength to capitalise on his opportunities, and eventually his demons won with his 1925 suicide.

Before this tragedy, he did make a run of 3 superb feature films in the U.S.. ‘Seven Years bad luck’, ‘The Three must Get There’s’ and ‘Be My Wife’, failed to win the audience they deserved to give Max a breakthrough to the big time. Despite this, they are really quite excellent. We showed a scene from seven Years bad luck that is an antecedent of the famous ‘mirror routine’ in Duck Soup. A masterpiece of timing and comic reaction, It went over a treat with the audience.

The other three ‘contenders’ were comics who flourished in short films, but never made it to features. Over time, feature films came to be seen as the acid test for greatness, but this wasn’t always the case. In the beginning, all comedy films were short. When Mack Sennett made the feature length ‘Tillie’s Punctured Romance’, they said it couldn’t be done. When Chaplin made ‘THE KID’ , publicity marvelled at the 6 reel picture “ upon which the famous comedian has worked a whole year!” If only they’d known how long it would later take him to make ‘CITY LIGHTS’.

Of course, Chaplin’s features were a great success; features became the norm. Shorts, over time, became the Cinderella. Today, the comics best remembered are the ones who took on the challenge of feature length films – carrying the fuller, more developed stories showed their skill, and these are indeed the films that endure the best.

However, there’s been this image of the comics in shorts, with a view that anyone who couldn’t make it in features was a lesser talent. That it was all just moustachioed men falling in water and flinging custard pies around like But shorts, in their own way, are a separate art form. To tell a story, keeping a constant ripple of laughter is no mean feat. I think it’s a good analogy to the classic sitcoms of the 70s. Dad’s Army, Porridge, Are You Being Served? They all tried to make feature versions, but they’re always disappointing. Some things are just better in miniature.

Of course, with so many thousands of shorts being turned out, yeah, there’s a lot of dreck. But there are also many, many gems, including some by our next three comedians.

Lloyd Hamilton was a comedian’s comedian. Keaton said he was, “one of the funniest men in pictures,”, while Mack Sennett said “[he] had comic motion. He could do nothing except walk across the screen, and still he’d make you laugh.” What appealed to fellow performers was his unique style of reactionary comedy; playing an overgrown mama’s boy, he relied less on mechanical gags and slapstick than reacting to an endless series of disasters that befell him. His comic equipment included a tottering walk ill-matched to his eternal sense of dignity, a silly pancake hat and a range of hilarious facial expressions. Hamilton could show disgust or disdain better than perhaps any other performer at that time. Oliver Hardy certainly picked up some hints for camera looks from him. Unlike many comedians, he didn’t especially need a strong strong storyline, just to have a really, really bad day! The titles of his films, such as ‘CRUSHED’, ‘LONESOME’ or ‘NOBODY’S BUSINESS’ reflect this; they sound more like Kafka novels than comedies!

Unfortunately, most of Hamilton’s best work went up in smoke years ago. Scattered examples do exist, but it was a challenge to find a film in projectable quality that represented him well. We had to settle for THE SIMP, an early, embryonic film in his canon. It’s not one of his very best, but has some good examples of his anti-hero style. For instance, there are some amusing gags involving him trying to get rid of a pesky dog (don’t worry, dog lovers, apparently the dog was his own and not hurt during filming). We were lucky to be able a newly reconstructed 22 minute version of THE SIMP compiled by David Glass. It didn’t get quite the laughs I’d hoped for, but was a rare treat to see nonetheless.

Here’s a better Ham film, 1926’s ‘MOVE ALONG’:

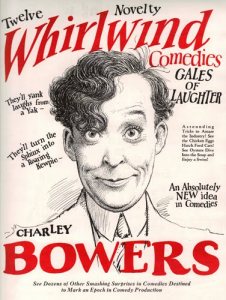

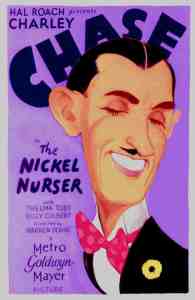

Our next comic was actually one of Lloyd Hamilton’s directors in his early days. Charley Parrott, or as he later became better known, Charley Chase, was one of the top comedy directors in the teens and early 20s. He had a happy berth working in this capacity at Hal Roach studios, before fate intervened. Harold Lloyd, Roach’s top star, left to produce independently. Now, Roach’s remaining comics were all very good, but none had the human appeal of Lloyd. Roach realised his talented, good-looking director might fit the niche perfectly and put him in a series of one-reelers.

From the get-go, Chase had his comic style in place. While he was slightly reminiscent of Lloyd, he actually owed more to Max Linder, an eternally embarrassed bon vivant fallen on hard times, always winding up in farcical situations. Chase could not have existed in his full capacity before the jazz age, though; he was especially interested in risqué gags and plotlines to heighten his character’s embarrassment, and the permissive ways of the late 20s gave him perfect opportunities to do so. A prime example of this is LIMOUSINE LOVE (1928), which we showed to a terrific response. It’s also a great forum for Chase’s ability to take a simple, everyday beginning to a story, then pile on loads of ridiculous, absurd complications, yet still have these plot twists seem believable. In LIMOUSINE LOVE, he is just a normal guy, heading to his wedding. He’s run out of gas though, and time is ticking on. While Charley goes off to find some gas, a young lady (Viola Richard) is soaked in a mud-puddle. Seeing his seemingly abandoned car on the country road, she hops in the back to change her clothes and dry off.

Charley returns, unaware of this, and drives off. Viola’s clothes fall out of the window, and he is left with a naked woman in the back of his car on the way to his wedding. Things go from bad to worse as he picks up a hitch-hiker, who of course, turns out to be her husband… Charley’s attempts to get rid of Viola without her husband or his fiancée knowing make up one of the funniest sequences in silent comedy.

Sadly, this film isn’t on YouTube, so here’s another. It’s another great example of Charley’s absurd, yet warm and believable stories. ‘MIGHTY LIKE A MOOSE’ (1926) is the story of a homely husband and wife who have plastic surgery to surprise each other. Trouble is, they then fail to recognise each other, and embark on an affair. This goofy sounding story actually seems totally natural when you see it told by Chase and director Leo McCarey. Throw in great performances, terrific set-pieces and you have one of the greatest silent comedies ever made. With shorts as good as this, who says features are better?

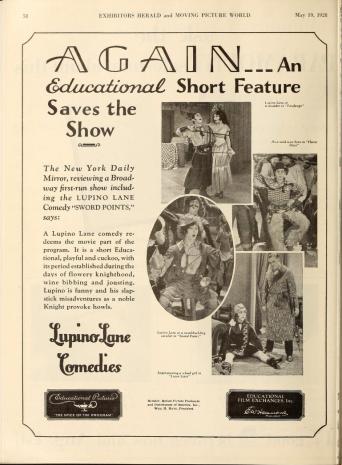

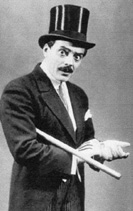

The talents of Lupino Lane were very different to Charley Chase. Lane was British, but born of a long line of entertainers tracing their roots back to 17th Century Italy. From the time he could walk, he had been trained in the rich pantomime tradition. He would later recall that, as a small child, his father made him sit in the splits for half an hour every day! All this training paid off; he was a master of comic timing, slapstick and acrobatics. Within seconds, he could backflip from a table, tumble across a room and fall into the splits, then raise himself up to standing position without putting so much as a hand to the ground. On film, he wore a perpetually startled expression enhanced by his huge eyes, almost as if these acrobatics happened by accident. A little chap, he used his size to contrast comically with the epic background his films placed him in: he might be a misfit gaucho, pirate, explorer or Mountie.

‘SWORD POINTS’ is his version of THE THREE MUSKETEERS, and is one of his best films. Even better, we were able to show it in a sparkling print that enhanced the whirlwind of gags and acrobatics.

SWORD POINTS has two centrepieces. The first relies not on acrobatics, but is a carefully constructed wine cellar sequence that showcases an alternative facet of the music hall comedian: an ability to squeeze any possible gag out of a handful of props and a simple task. Here, Lane is sent to the wine cellar to fetch some tankards of wine. Over the course of the next few minutes, he manages to get all his hands and feet stuck in jugs, and flood the wine cellar, eventually swimming off with the tray of tankards atop his head.

The second is a maelstrom of rolls, flips and trips through some secret trapdoors, which also packs in some amusing take-offs on Fairbanks’ casual swashbuckling style. The speed and energy of these scenes must be seen to be believed. Sadly, ‘SWORD POINTS’ is another film not on the ‘tube, but Lane turned out dozens of these great little films. Here’s FANDANGO, also from 1928, and another good ‘un.

Lane’s talents were probably better off in short films than stretched across a full feature film. However, as I’m sure the Kennington audience would agree, he was still an incredible comedian and acrobat. The other silent contenders, in their own ways, were all real individuals whose efforts to bring laughter to the world deserve better remembrance. It was a pleasure to share them, both at The Cinema Museum, and here, with some new audiences.