From the archives, here’s an article that first appeared in issue #13 of The Lost Laugh, in 2021…

DOUBLE TROUBLE: THE SNUB POLLARD & MARVIN LOBACK FILMS

One of my earliest memories of silent comedy is of watching a ‘COMEDY CAPERS’ VHS when I was very young. One of the episodes on the tape, ‘BABY BACHELOR’ confused me: it was a virtual copy of Laurel and Hardy, but the Laurel character was wearing an enormous moustache. Who were these L & H wannabes? Years later, I learned that they were Snub Pollard and Marvin Loback, jumping on the bandwagon of fat-and-skinny comedy teams as Stan and Babe were at their zenith. I’ve always been intrigued by these copycat shorts, and endeavoured to find out more about them. Here’s the story…

It’s late 1927. Laurel & Hardy’s pairing has blossomed, and they’ve just produced their biggest hit to date, THE BATTLE OF THE CENTURY, for Hal Roach. For another ex-Roach employee, Snub Pollard, things are not going so well. Once one of the studio’s big stars in classics like IT’S A GIFT and SOLD AT AUCTION, he had been let go as the studio moved to more sophisticated comedy. A series of shorts at the low-budget Weiss Brothers studios was a step down the ladder; even further down was a return to vaudeville when that series ended.

While Snub was treading the boards, Laurel and Hardy’s meteoric rise gave someone at Weiss Brothers a brainwave: why not produce their own version of the team, with Snub as the thin half? Pollard was called back to Weiss Brothers in early 1928, and teamed with large comic Marvin Loback. Loback was a veteran of Sennett and Roach, and had even appeared with Snub a few times in small parts.

The films that resulted might charitably be called homages to Laurel & Hardy; less kindly, they could be called blatant rip-offs. To be fair, some of the films were more original than others, and there was always a certain amount of shared ground and gag-borrowing in silent comedy. However, the way that some of the Pollard-Lobacks like SOCK & RUN re-enact whole chunks of L & H films is particularly shameless. What particularly attracted attention is the one-time belief that these shorts were made before the Laurel & Hardy films they resemble. We now know this to be untrue. However, there do seem to be some examples where the Pollard films did a gag or routine simultaneously or before the Roach crews.

The films are an interesting sidelight in Snub’s career, and a fun curio for L & H fans. The Laurel & Hardy influence is obvious from the outset, but is painted broadly: the amount of nuance may be gauged from the fact that Loback’s character is called ‘Fat’. There’s none of Oliver Hardy’s quiet dignity in that! To be fair, Loback does a decent job throughout the series of replicating Hardy’s impatience, if not his charm. It’s his presence that really brings the L & H comparison. As for Snub, he hasn’t changed his appearance from his standard costume of bowler, moustache, striped shirts and spats. As far as his performance goes, he’s definitely gone a bit more passive, but his trademark moustache is a handicap in reproducing Stan’s blank innocence. He rarely does a complete rip-off of Laurel mannerisms (although he does a crude version of the cry in one film), but the intention is clear.

Though the first few films of the series mainly aped L & H in the comic’s appearance, soon more similarities began to creep in. Perhaps it was lack of inspiration for new material, but the intentional effort to piggyback on the team’s success soon becomes a bit more blatant by –ahem- borrowing their material. Sometimes the likenesses are vague – Snub and Marvin as two sailors in HERE COMES A SAILOR, or a hint of DOUBLE WHOOPEE in MITT THE PRNCE, for instance. At other times, the similarities constitute plagiarism pure and simple, as entire gags and plots are ripped from L & H films like FROM SOUP TO NUTS, PUTTING PANTS ON PHILLIP and SHOULD MARRIED MEN GO HOME!

The L & H connection has brought the Pollard-Loback films into focus now and again, particularly when one theory suggested the films actually pre-dated the Laurel & Hardy films! In the pre-Internet days, and before the onset of trade paper archives like the Media History Digital Library, States-Rights films made by companies like The Weiss Brothers were obscure and hard to trace. As a result, the films seem to have been confused with Pollard’s first (solo) Artclass series, which were made in 1926-27. We now know that the Pollard – Lobacks were released in two batches, six films in 1928-29, and a further four in 1929-30, disproving the claim that Laurel & Hardy were the ones doing the borrowing.

The trade magazines only gave light coverage to low-budget, indie two-reelers like these, but after sifting through, I’ve gathered a handful of more precise dates. British trades like The Bioscope and Kinematograph Weekly also came in handy – though the films generally hit the UK a little later, the release dates gives a rough indication of when they were made and registered for release. Below is the information I’ve been able to gather to pin down the dates and titles a bit more.

1928 -29

Variety reported that Snub was working for Artclass on May 2, 1928. By June 19, they note that both Pollard and Ben Turpin have finished filming their first shorts for the company (THICK & THIN and SHE SAID NO, respectively). By September 1st, 1928, Film Daily reports that an additional two films are ready: ONCE OVER & THE BIG SHOT. American mentions of the series are scant hereafter. However, the British Press picks up the slack. Louis Weiss visited London to trade-show the series in the Autumn and they were distributed by Gaumont from November 1928. The Films Act, article 6 required that all films must be registered for exhibition – these listings tells us that the other three films from the first series were SOCK & RUN, MEN ABOUT TOWN and HERE COMES A SAILOR.

1929-30

In May 1929 Film Daily reported that Snub listed four titles in production for 1929-30; however, the titles listed were actually ones from the previous season, presumably an error. Actually, the four films were DOUBLE TROUBLE, NO KIDDING, SPRINGTIME SAPS and MITT THE PRINCE. These were released with synchronised music tracks (but no dialogue) as a concession to the advancing sound revolution. Adverts exist for the reissue of these films, with soundtracks, in 1943.

All the films were filmed in the Spring of 1929, with Variety reporting that the series wrapped in the second week of May, 1929. DOUBLE TROUBLE was used to launch the second series, and was reviewed in Film Daily on August 18th, 1929. SPRINGTIME SAPS was reviewed on October 24th. In Britain at lease, MITT THE PRINCE was the last of the series to be released, in February 1930.

With the above in mind, here’s a run-down of these seldom-discussed films, in what I believe is the order of release.

- THICK & THIN

THICK & THIN was definitely the first of the shorts to be released and sets the tone for the series, with Snub and Marvin as two penniless gents in a shabby boarding house, trying to cook a meal, and then sneaking their belongings out without paying the rent.

Of all the series, this is the one that most harks back to Snub’s Hal Roach films, the hidden devices that the pair use to cook their meal a bit like a less elaborate reminder of IT’S A GIFT, STRICTLY MODERN and other films featuring Snub gadgetry.

There’s also a bit of a Harry Langdon influence, both in Pollard’s subdued persona, and in a gag lifted from Langdon’s FIDDLESTICKS. THICK & THIN is undoubtedly derivative, but the gags flow nicely and it’s an entertaining little two-reeler.

2. ONCE OVER

Snub and Marvin roll into town on a freight train, riding in a boxcar of cows. There’s a funny scene featuring the atrociously fake cow heads they use as a disguise, confounding brakeman Tiny Lipson (even more so when one of the cows appears to smoke his cigar!). For a topper, they exit the boxcar under blankets that make them appear to be a strange, two-headed beast!

The bulk of the film centres around their attempts to filch some food, pursued by cop Harry Martell. Along the way, two Hal Roach gags are – *cough* – borrowed. The scene from THE FINISHING TOUCH with Stan Laurel on both ends of the same plank is used, and there’s also a gag with a mailbag and a fence lifted shot-for-shot from Max Davidson’s DUMB DADDIES

Then it’s on to the park, where they fail to steal a family’s picnic before Snub has a brainwave. Covering his hand with a long white sock, he hides in a bush and pretends to be a swan, stealing the sandwiches a lady is feeding to the birds. Unfortunately, he knocks her in the water, and the cop is on their trail again. To elude him they enter a restaurant and are put to work as waiters. A predictable level of competence ensues, and things wrap up with some pie-throwing. Though the finish is weak, ONCE OVER is maybe the best of the Pollard-Lobacks. The borrowing is less overt than in many of the other shorts, and the film rambles along happily from one gag situation to the next, with some nice original ones thrown into the mix.

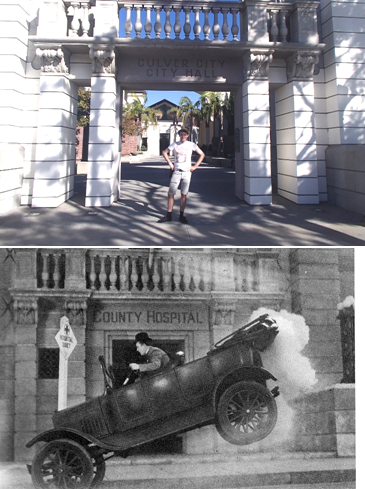

3. THE BIG SHOT (Released October 1928, belatedly reviewed in Film daily, Feb 1929)

THE BIG SHOT is another one of the better Pollard-Lobacks, having some semblance of following the same story from start to finish. Snub and Marvin are reporters tasked with getting a photo of a camera-shy Scottish inventor. This involves Snub being coerced into wearing a kilt, and we’re into a semi re-run of PUTTING PANTS ON PHILIP. It doesn’t work on the same level of the L & H film – the sexual ambiguity surrounding the innocent Laurel character in PHILIP just cannot translate to a character wearing a huge moustache! To be fair, the gags don’t try to be a carbon copy and mainly just deal in the incongruity of Snub’s appearance. There are a few nice original variations, including Snub trying to change a tyre, with the draught from every passing car sending his kilt flying up. Snub and Marvin wind up following the inventor onto a boat and eventually corner him for a photo, but Snub is too generous with the flash powder and after a huge explosion, he is left clinging to the mast.

4. MEN ABOUT TOWN

After three films that borrowed from Laurel & Hardy but at least tried to have original plots, the Pollard unit pretty much gave up the pretence of trying to be original for the next few films.

MEN ABOUT TOWN is largely a re-run of SHOULD MARRIED MEN GO HOME set on the golf course, with added gags from YOU’RE DARN TOOTIN’. However, there are some occasional moments in the Weiss Bros films where they seem to foreshadow a later Laurel & Hardy moment. Here, Marvin’s attempts to contact Snub and sneak him out of the house include trying to contact him by phone, anticipate L & H’s BLOTTO of 1930. However, L &H knew how to milk the scene for all it was worth, whereas here it is just a quick throwaway gag. MEN ABOUT TOWN is definitely one of the weaker films in the series.

5. SOCK & RUN

Ok, now they’re really taking the Mickey. Not content with pinching the kilt material from PUTTING PANTS ON PHILIP, they basically re-film the entire first reel of that film, throwing in some soup gags from YOU’RE DARN TOOTIN’ and ending with a boxing match á la BATTLE OF THE CENTURY!

The PHILIP material is recreated gag for gag, from the laughter of the crowd as Snub arrives, to his medical examination, to Marvin’s attempts to keep him walking a few paces behind. Oh, but wait, it’s actually been changed – Snub is French, not Scottish, and people are laughing at his silly top hat instead of his kilt. That ought to avoid the copyright infringement lawsuit…

Of all the Pollard-Lobacks, SOCK & RUN is maybe the one that has most secured the reputation of the series as being mindless L & H rip-offs. In this sense, it’s the worst of the bunch. On its own terms, it’s not terrible, and if you’d never seen a Laurel & Hardy picture, you’d probably find it entertaining. But if you lived in a world without Laurel & Hardy, SOCK & RUN would be the least of your problems.

6. HERE COMES A SAILOR

HERE COMES A SAILOR starts out with the boys as sailors who hire a car, in the spirit of TWO TARS, but doesn’t get down to mass car destruction (something Weiss Bros surely didn’t have the budget for). Instead, it takes a left turn to become a clone of FROM SOUP TO NUTS as the pair get jobs at a dinner party, down to Snub serving the salad “undressed”.

There is one nice original gag, as Snub accidentally causes a cameraman’s tripod camera to collapse on top of him; bumbling around on all fours with the cloth over his back and the lens dangling out in front, the man resembles some strange elephantine creature!

7. DOUBLE TROUBLE

Snub and Marvin unsuccessfully rehearse and audition their terrible vaudeville act, then are hired as process servers to repossess their landlord’s piano. This second series of Pollard-Lobacks are where some of the confusion over their originality seems to have come from. While the first-series L & H rip-offs like SOCK & RUN are blatant steals, the second batch do actually contain some gags or situations used by Pollard & Loback before Laurel & Hardy. DOUBLE TROUBLE is a case in point; Snub and Marvin’s attempts at repossession anticipate BACON GRABBERS, not just in story, but also down to individual gags.

Held back until after L & H’s first few talkies, BACON GRABBERS wasn’t released until October 1929, but DOUBLE TROUBLE was filmed before May, and had already been released and previewed by August of 1929. Therefore, it couldn’t have been a simple case of Les Goodwins or other Weiss gagmen having been to see the latest L & H film at their local theatre and filling their notebooks with ideas.

However, while DOUBLE TROUBLE may have reached cinemas before BACON GRABBERS, the Laurel & Hardy film was almost certainly finished first. My theory is that a Roach gagman moved over to Weiss Brothers, probably during the time when the Roach studios were being fitted out for sound. Another possible ‘mole’ was Bert Ennis, Snub’s gag and title writer. Ennis doubled as a publicist, and had his own regular column in Motion Picture Classic, so was probably quite well connected with other studios.

8. NO KIDDING (September 1929)

NO KIDDING is a fun little short, featuring Snub and Marvin accidentally in charge of a toddler, and then having to hide him from the landlord of their bachelor apartment. The toddler is actually played by midget Billy Barty (incidentally, he played a similar role in the Laurel-Hardy SAILORS BEWARE). There are some amusing scenes as they disguise the toddler as an adult in a suit, complete with cigar, but the deception is undermined as he proceeds to make various noises and arouse the landlord’s suspicion.

Again, there’s a parallel situation of the Snub film seeming to pre-empt the Laurel & Hardy film. The central situation of the team hiding an unwanted guest in their apartment was also the basis of ANGORA LOVE, and one particular gag appears in both films. As the landlord lectures Snub & Marvin/Stan & Ollie that “this is a respectable boarding house”, a woman walks behind him towards her room, pursued by a sailor! NO KIDDING was filmed in early Summer 1929, and released in the Autumn, but ANGORA LOVE wasn’t released until December 1929. The Roach Mole seems to have been at work again…

(By the way, this is the short I saw on COMEDY CAPERS VHS, cut down and retitled…)

9. SPRINGTIME SAPS (October 1929)

SPRINGTIME SAPS is a ragbag effort that changes situations as the team run out of gags for each one. The best scenes are set in the park, with Snub and Marvin attempting to get 40 winks on a bench before being woken by a cop, and then trying to steal a man’s cigar.

When that’s milked for all the comedy they can manage, the pair get jobs as taxi drivers, mainly so that they can nab a gag from the Sennett film TAXI DOLLS. Then things peter out in some feeble haunted house comedy.

The most notable aspect of this film is a moment where a man angrily gives Snub the middle finger! It’s not a slip or even made to seem like one – it’s just blatantly there, in full shot! It shows how low under the radar these states-rights films must have flown, particularly at the tail end of the silent era.

10. MITT THE PRINCE (Release dates variously quoted as Dec 1929 and Feb 1930).

Snub and Fat are two incompetent handy men. Sent to deliver some parcels to the social-climbing Mrs Woodby-Noble (Ho Ho!), they write off the car on the way there with bit of L & H patent tit-for-tat. When the Prince who is supposed to attend fails to show, the hostess persuades Snub to take his place. There’s a vague hint of DOUBLE WHOOPEE in this premise, but no direct stealing of material.

The best thing about MITT THE PRINCE is a nice running gag of Snub accidentally getting his hand continually in others’ pockets; other than that, it’s a middling effort.

The series wrapped in May of 1929, and with it Snub’s career in silents. However. there was still one last gasp for his starring career, and his association with Weiss Brothers. In July 1929, Film Daily reported that the company was planning some talkie shorts, with Snub heading east to film some. Two shorts resulted, and the Pollard-Loback faux L & H vibe was dropped:

HERE WE ARE (filmed July 1929, released August 1929 )

Snub played a plumber’s assistant, who ends up pretending to be the plumber’s wife. Obviously, he didn’t wear his moustache in this one, or the deception wouldn’t have been very convincing!

PIPE DOWN (Trade shown September 1929)

Snub was teamed with Jack Kearney as a pair of sailors on shore leave who keep running afoul of tough guy Gunboat Smith, ending in a slapstick fight. After Kearney knocks smith unconscious, the pair light cigarettes, but an open gas lamp next to them causes a huge explosion. At least Snub’s starring career ended with a literal bang! Variety wasn’t impressed, calling PIPE DOWN “third-rate Vaude stuff passed off as film comedy”.

These two talkies were released in the UK in February, 1930.

And with that, the Snub Pollard Weiss Brothers series was over. The films were hardly his most glorious moment, but they helped keep his starring career afloat a little longer. Viewed today, the films range from good fun, to middling, to outrageous rip-offs (sometimes within the space of the same film!), but they show an interesting sidelight to how silent comedians could try to meet changing tastes and demand for particular styles of comedy. They are also a reminder of how special, and how hard to replicate, the chemistry between Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy was.

You can enjoy some of Snub’s Weiss Brothers films (and a host of others from the studio, including Ben Turpin and Jimmy Aubrey) in the great DVD WEISS-O-RAMA

For more on Snub, check out the whole issue #13 of THE LOST LAUGH MAGAZINE here…

It came! After weeks of waiting for Trans-Atlantic deliveries to return to normality, yesterday HARRY LANGDON AT HAL ROACH: THE TALKIES 1929-30 finally dropped into my mailbox.

It came! After weeks of waiting for Trans-Atlantic deliveries to return to normality, yesterday HARRY LANGDON AT HAL ROACH: THE TALKIES 1929-30 finally dropped into my mailbox.

Charley Chase has gone from being an under-represented figure on home video releases to having much of his classic work out there in superior quality. Thanks to DVD releases from Kino, AllDay Entertainment and Milestone films, a majority of his existing silent work can now be widely seen. In recent years, even his late sound shorts for Columbia have even been pulled from the vaults and released by Sony.

Charley Chase has gone from being an under-represented figure on home video releases to having much of his classic work out there in superior quality. Thanks to DVD releases from Kino, AllDay Entertainment and Milestone films, a majority of his existing silent work can now be widely seen. In recent years, even his late sound shorts for Columbia have even been pulled from the vaults and released by Sony. LOOSER THAN LOOSE, a charming romantic situation comedy, where much of the humour is down entirely to the wonderful performances of the cast;

LOOSER THAN LOOSE, a charming romantic situation comedy, where much of the humour is down entirely to the wonderful performances of the cast; On-screen, he is an odd creature to be sure; his slithery, amphibious movements inside oversized clothes and a bucket-shaped hat give him the appearance of a strange, giant newt. His saucer-shaped eyes and slow blink anticipate a little of Langdon, but nothing else indicates any real kind of character. HIS BUSY DAY, as its title suggests, was a fairly generic little trifle, with parks, pretty girls, pies and a lack of continuity: Toto steals a pie, dresses as a woman to escape a policeman, gets a job as a newsreel cameraman for a bit, then gives it up after he angers the newsreel proprietor (Bud Jamison). Even allowing for some missing footage, this was clearly a fairly run of the mill effort. Toto did have good timing however, as the highlight of the film showed: a scene where he hides from Bud Jamison behind a pivoting wooden sign, at one point attaching himself to it in the splits position! Ultimately, Toto’s biggest contribution to film comedy was in leaving films, thus opening the door for Roach to hire a young Stan Laurel as his replacement.

On-screen, he is an odd creature to be sure; his slithery, amphibious movements inside oversized clothes and a bucket-shaped hat give him the appearance of a strange, giant newt. His saucer-shaped eyes and slow blink anticipate a little of Langdon, but nothing else indicates any real kind of character. HIS BUSY DAY, as its title suggests, was a fairly generic little trifle, with parks, pretty girls, pies and a lack of continuity: Toto steals a pie, dresses as a woman to escape a policeman, gets a job as a newsreel cameraman for a bit, then gives it up after he angers the newsreel proprietor (Bud Jamison). Even allowing for some missing footage, this was clearly a fairly run of the mill effort. Toto did have good timing however, as the highlight of the film showed: a scene where he hides from Bud Jamison behind a pivoting wooden sign, at one point attaching himself to it in the splits position! Ultimately, Toto’s biggest contribution to film comedy was in leaving films, thus opening the door for Roach to hire a young Stan Laurel as his replacement. of independent comedies and also working as a director. ‘SWEET DADDY’ was a simple tale of a henpecked husband who seizes his hour of freedom when sent out for the groceries, but it was full of some great gags, and snappily directed by Perez. Particularly there was a charming sequence in which he gazes at a girl on a poster, who seems to come to life and flirt with him. Perez’ career was sadly coming to an end; cancer cost him a leg in 1923, and while he continued as a director, the illness returned and took his life in 1928. Nevertheless, he was obviously a real talent, and it’s been mainly due to the efforts of Steve Massa and Ben Model that we’re able to see his films again: they’ve put together

of independent comedies and also working as a director. ‘SWEET DADDY’ was a simple tale of a henpecked husband who seizes his hour of freedom when sent out for the groceries, but it was full of some great gags, and snappily directed by Perez. Particularly there was a charming sequence in which he gazes at a girl on a poster, who seems to come to life and flirt with him. Perez’ career was sadly coming to an end; cancer cost him a leg in 1923, and while he continued as a director, the illness returned and took his life in 1928. Nevertheless, he was obviously a real talent, and it’s been mainly due to the efforts of Steve Massa and Ben Model that we’re able to see his films again: they’ve put together Next up was ‘SEVEN YEARS BAD LUCK’ (1921), perhaps Max Linder’s best feature. It’s now famous for having one of the best versions of that broken mirror routine, some 12 years before the Marx Brothers’ DUCK SOUP, but the whole film is most entertaining. David Robinson’s introduction paid a heartful tribute to Max’s daughter Maud Linder, who passed away last year. It was her zealous promotion of her father’s talents that has ensured he is still remebered today, almost 100 years after his death.

Next up was ‘SEVEN YEARS BAD LUCK’ (1921), perhaps Max Linder’s best feature. It’s now famous for having one of the best versions of that broken mirror routine, some 12 years before the Marx Brothers’ DUCK SOUP, but the whole film is most entertaining. David Robinson’s introduction paid a heartful tribute to Max’s daughter Maud Linder, who passed away last year. It was her zealous promotion of her father’s talents that has ensured he is still remebered today, almost 100 years after his death.

We finished off in fine style with some audience participation for Laurel & Hardy’s YOU’RE DARN TOOTIN’, in which the pants-ripping finale was replicated through the ripping of newspapers placed under each chair in the auditorium. This programme was great fun, and a real variation on the usual silent film accompaniment. No kazoos were hurt during the screening of these films.

We finished off in fine style with some audience participation for Laurel & Hardy’s YOU’RE DARN TOOTIN’, in which the pants-ripping finale was replicated through the ripping of newspapers placed under each chair in the auditorium. This programme was great fun, and a real variation on the usual silent film accompaniment. No kazoos were hurt during the screening of these films. knowledge for the old comedians. Among the highlights were clips from Tati’s MON ONCLE, Lupino Lane’s JOYLAND, and Roy’s own semi-silent film ‘THE MALADJUSTED BUSKER’. Finally, we concluded with a full showing of the complete ‘BATTLE OF THE CENTURY’. I’ve written about this film before, but it was as marvellous tonight as the first time I saw the ‘new’ footage; simply one of the iconic silent comedy scenes, now once again “as nature intended”.

knowledge for the old comedians. Among the highlights were clips from Tati’s MON ONCLE, Lupino Lane’s JOYLAND, and Roy’s own semi-silent film ‘THE MALADJUSTED BUSKER’. Finally, we concluded with a full showing of the complete ‘BATTLE OF THE CENTURY’. I’ve written about this film before, but it was as marvellous tonight as the first time I saw the ‘new’ footage; simply one of the iconic silent comedy scenes, now once again “as nature intended”.